Canterbury resident Vince Farley had a 30-year career in the Foreign Service, serving tours in U.S. embassies in Niger, South Korea, Mauritania, Yugoslavia, and Cote d’Ivoire, as well as in Washington, DC. His last posting was as Diplomat-in-Residence at the Carter Center, advising former President Carter on Africa. He accompanied President Carter on eight missions to Africa focused on conflict resolution, spending a total of 51 days flying in a small Challenger jet. Vince has enough stories from a ten-month (1995–1996) peace initiative to fill a book, but here he recounts one day’s experience in Goma, Zaire. This story highlights President Carter’s fearless, risk-taking approach to the search for peace. It is written to honor President Carter for his 100th birthday.

Arriving in refugee camp, Zaire. Heads of state meeting in Cairo.

A November 1995 visit to Goma, eastern Zaire, was part of President and Mrs. Carter’s seven-day visit to eastern Africa in preparation for the late November Great Lakes Summit in Cairo. The focus of the visit to Goma was one of the refugee camps of Rwandans who had fled Rwanda after the genocide, to meet with leaders of the exiled Rwanda community, and to meet with leaders and representatives of the Zairian community in Goma.

In September, President Carter had met with President Museveni in Entebbe, Uganda, and then with President Mobutu of Zaire in Faro, Portugal (at these meetings, Presidents Museveni and Mobuto each designated a close advisor to work with President Carter on this initiative, and President Carter designated me to be his personal representative). Subsequently, both presidents accepted President Carter’s invitation to meet in New York in October—surprisingly, the two presidents had never met in person. At that October meeting, the two African presidents issued a joint press release asking President Carter to come to the region and chair a process to address the crisis created by the one million Rwandan refugees in Zaire and also work to resolve the underlying political issues between the nations in the Great Lakes region. President Carter accepted the request and issued a press release outlining the projected peace process.

After many discussions and exchanges of letters with the presidents of the Great Lakes countries and their key advisors, the presidents of Uganda, Zaire, Rwanda, Burundi, and Tanzania accepted President Carter’s invitation to a summit of the presidents in Cairo in late November. President Carter invited former Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere and Bishop Desmond Tutu of South Africa to be co-facilitators.

After meetings with the heads of state in their capitals, we flew to Goma, eastern Zaire. As we walked from the plane to the motorcade, the head Secret Service agent told me to stay tight inside the bubble the Secret Service would have around President and Mrs. Carter and also not to make any sudden moves, as the security situation was tense and there were many armed individuals in the area. We boarded several vans to visit one of the major refugee camps, which had several hundred thousand refugees encamped several kilometers from the Rwandan border. As President Carter’s trip had been publicly announced about 10 days before the trip, I had been told that many leaders of the exiled Rwandan community, including some key leaders flying into Goma from Europe and elsewhere, would be attending President Carter’s meeting.

Heads of state, President Carter, and co-facilitator Bishop Desmond Tutu.

Our motorcade to the refugee camp included perhaps 10 Secret Service agents, double the number at most stops in a visit of President Carter, and some Zairian military, perhaps a detachment in three or four vehicles. When we arrived at the refugee camp, we were escorted into a tent set up for the meeting. At one end of the tent was a head table where President Carter, Mrs. Carter, and I sat. Directly in front of us were about three rows of folding chairs set up for the senior Rwandans—about 20 people—and behind these chairs another 15 or so rows of chairs. Secret Service agents stood at the entrance to the tent near the head table and at the entrance at the far end of the tent.

I noted that some Zairian military had taken positions outside the tent. President Carter opened the meeting by describing the Carter Center Great Lakes Initiative to address the crisis in Zaire and the Great Lakes region and mentioned his recent meetings with the presidents of Uganda, Zaire, Rwanda, and Burundi. He then described his visit to Rwanda, where he had visited the sites where hundreds of thousands of Rwandans who had been killed in the genocide were buried. He then leaned forward and said, “I know many of the leaders of this genocide are in this room, and I want to assure you that you will be brought to justice.”

Realizing that with that statement, we could be in a precarious situation, out of the corner of my eye, I glanced at the Secret Service agent at the door near our table, wondering about the contingencies the Secret Service had set up to extricate us from a camp of several hundred thousand refugees, using the Secret Service detail of 10 and perhaps 25 Zairian soldiers. The leaders in the front row did not react to President Carter’s statement and, stone-faced, sat in silence, not exhibiting any emotions. President Carter continued his comments, which were followed by questions from the Rwandans in the room. There were no comments on President Carter’s statement regarding the “génocideurs” in that tent being brought to justice.

President and Mrs. Carter flanked by President and Mrs. Mobutu.

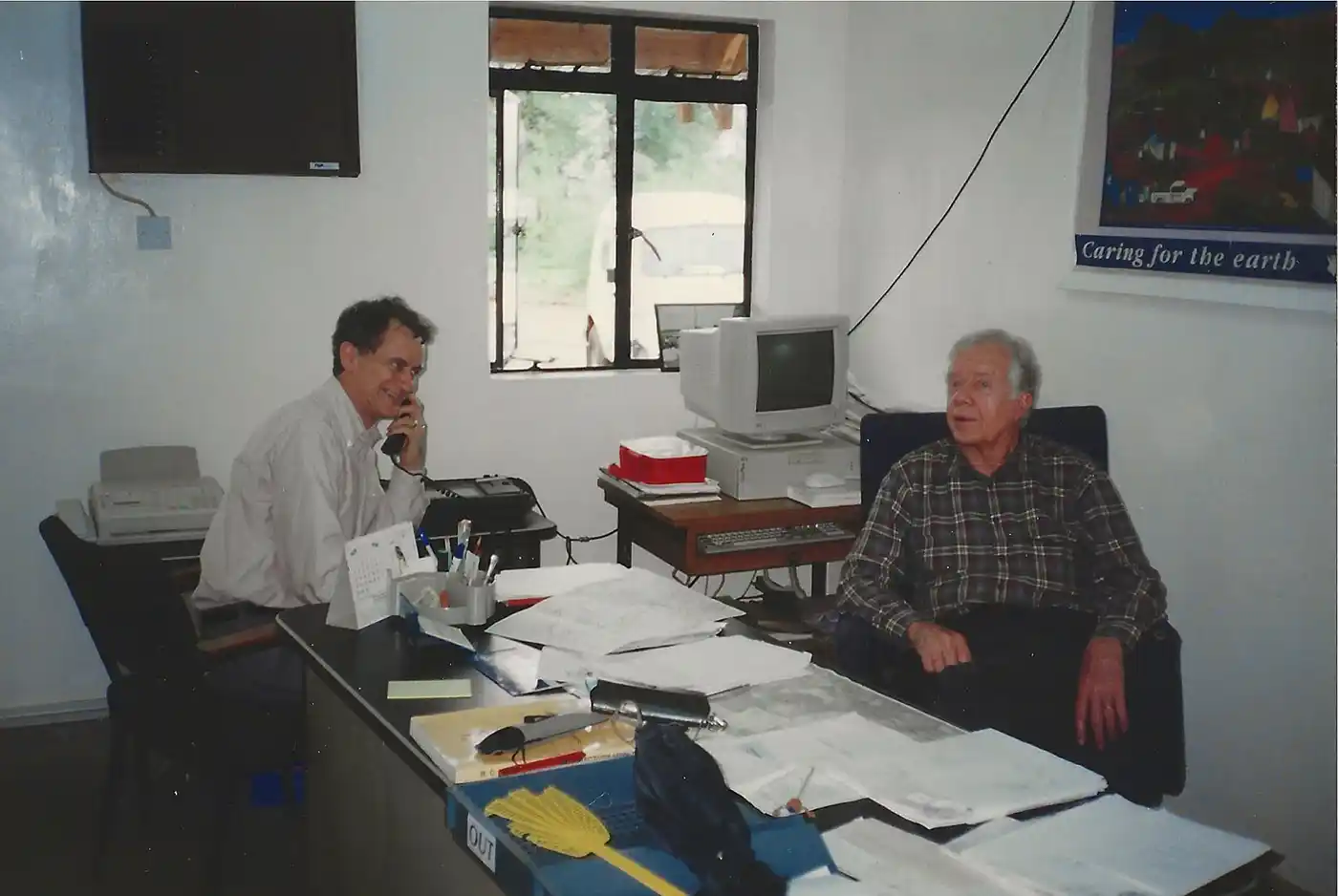

At the end of each day of a trip with President Carter, I usually met with the Secret Service agents, and President Carter’s longtime scheduler, to review the day’s activities and plans for the next day. Over cold beers, after a hot day, we discussed the meeting at the refugee camp. The agents noted that President Carter had made a provocative statement, and we agreed that we were a bit surprised by the lack of reaction from the Rwandan leaders at the 7 be in a precarious situation, out of the corner of my eye, I glanced at the Secret Service agent at the door near our table, wondering about the contingencies the Secret Service had set up to extricate us from a camp of several hundred thousand refugees, using the Secret Service detail of 10 and perhaps 25 Zairian soldiers. The leaders in the front row did not react to President Carter’s statement and, stone-faced, sat in silence, not exhibiting any emotions. President Carter continued his comments, which were followed by questions from the Rwandans in the room.

President Carter greeting Rwandan President Pasteur Bizimingu; to President Carter’s right is Vice President Paul Kagame, who is now president.

There were no comments on President Carter’s statement regarding the “génocideurs” in that tent being brought to justice. At the end of each day of a trip with President Carter, I usually met with the Secret Service agents, and President Carter’s longtime scheduler, to review the day’s activities and plans for the next day. Over cold beers, after a hot day, we discussed the meeting at the refugee camp. The agents noted that President Carter had made a provocative statement, and we agreed that we were a bit surprised by the lack of reaction from the Rwandan leaders at the meeting. The head of the Secret Service detail said that he had made many contingency plans regarding security. He told me that he had hired a heavy tanker truck filled with water to drive in front of our motorcade to assure that there were no mines planted in the roadway. At the end of our discussion, one of the Secret Service agents, who happened to be Black, told me, in jest, that for a split second at the refugee meeting, he wondered if he would be forced to take off his jacket and blend in with the mass of hundreds of thousands of Africans at the camp.

The summit of five African heads of state in Cairo was historic and resulted in a seven-month period of peace. I came to know President Carter as a man of courage who would not hesitate to take on any challenge in the pursuit of peace even though there could be risks or threats involved in the mission. I can’t think of any individual who was more deserving of the Nobel Peace Prize.

—Vince Farley

Vince Farley, Secret Service agents, and President Carter’s longtime scheduler Nancy Konigsmark at day’s end.